Click a button to download a PDF version of Chapter 1

or scroll down to read online.

The voluntary carbon market (VCM) is where private individuals and organizations issue, buy, and sell carbon credits outside of regulated or mandatory carbon pricing instruments. Carbon credits are tradable instruments transacted in the VCM. They are generated by activities that remove greenhouse gases (GHGs) from or prevent GHGs from being emitted to the atmosphere. Each credit in the VCM represents one ton of carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e) that is sequestered or has not been emitted. Carbon dioxide equivalents are a measurement unit that converts the global warming potential of any GHG into the reference GHG potential of carbon dioxide.

The VCM aims to mitigate climate change by creating space for private actors to finance activities that remove GHG emissions from the atmosphere or reduce GHG emissions associated with industry, transportation, energy, buildings, agriculture, deforestation, or any other aspect of human life.

Companies, governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and other public and private stakeholders participate in the VCM. Companies participate in the VCM to invest in activities that generate tradable GHG credits, to acquire credits to voluntarily offset GHG emissions, or to otherwise support climate change mitigation through financing activities that reduce GHG emissions or remove GHGs from the atmosphere. Companies participate in the VCM to contribute to their climate goals, to differentiate from competitors, to build brand recognition and consumer loyalty, and to define and market “carbon neutral” products.

Local communities, private landowners, subnational governments, and other stakeholders engage in the VCM through activity development and as beneficiaries of climate change mitigation activities. For NGOs, communities, and private activity developers, the VCM offers the opportunity to access finance—often in hard currency—to implement projects that reduce GHG emissions or enhance GHG removals. Governments can use the VCM to attract foreign direct investments and achieve additional climate change mitigation through VCM finance. A number of governments have developed programs that generate verified emission reductions and removals in the context of Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation plus (REDD+), and government agencies have sponsored VCM project activities in a range of other sectors. The instruments formulated under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement offer additional opportunities for governments to access finance for climate action.

How does the VCM work?

Carbon credits transacted in the VCM are issued and certified according to requirements set by carbon crediting programs or “carbon standards.” Carbon standards are rules and requirements set by private standard organizations—typically international NGOs—that establish the methodologies and verification, validation, and monitoring procedures that VCM activity developers must follow to certify that the activities measurably sequester or avoid GHG emissions.

The Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) is by far the largest standard. As of June 2023, VCS has issued 71.3 percent of the carbon credits in the VCM. The Gold Standard (GS) is the second largest, having issued 16.7 percent of credits. The third, fourth, and fifth largest standards are ACR (6.3% of credits), Climate Action Reserve (CAR – 5.1%), and Plan Vivo (PV – 0.5%).

Carbon credits that are traded in the VCM are generated by projects, bundles of projects, programs, or public policies. A project is a specific activity that removes or reduces GHG emissions in a specific sector following a standard-approved methodology. VCM activities are implemented at the project level and, in the case of REDD+, at the jurisdictional level. Projects and jurisdictional programs are defined in a geographic location over a period of time and approved, validated, monitored, and verified by a carbon standard.

Some carbon standards allow the aggregation of projects in grouped projects or in programs of activities. ‘Grouped projects‘ or bundles of activities under the VCS aggregate multiple projects engaged in the same activity into a single project. This enables programs that involve a high number of small projects to grow in scale without seeking full new validations from carbon standards for each expansion. A program of activities – as defined by the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and applied by the GS – is a set of multiple project activities registered as a single project activity in a defined geographic area with shared methodologies for project design and monitoring. Jurisdictional programs—often developed in the context of REDD+—are government-led GHG reduction programs and account for emissions reductions and removals at the national or subnational scale.

In general, projects, programs, and groups of projects or programs can be referred to as “VCM activities” or “climate change mitigation activities.”

Credits generated by VCM activities may be sold by project developers or government agencies directly to buyers or sold to intermediaries who then market carbon credits to final users. To transact carbon credits, activities need to be designed, developed, and certified; GHG emission reductions and removals need to be monitored, reported, and verified; and carbon credits need to be issued and transferred. In parallel, VCM activity developers need to attract and structure investment into the activities that reduce or remove emissions. The VCM may be segmented by sector or type of activity (e.g., forestry, land use, agriculture, renewable energy, waste), by the crediting standard (e.g., VCS or GS), by the credit quality (e.g., credits with community or other benefits), or by the year in which a credit was produced (i.e., the credit vintage).

How did the VCM start?

The idea of private companies offsetting GHG emissions with carbon credits emerged in the late 1980s. The first known carbon offset deal was an investment by the American energy company AES in a project run by the NGO CARE in Guatemala, in which AES provided finance for farmers to plant trees. This was followed in the mid-1990s by the launch of the Environmental Resources Trust (later rebranded the American Carbon Registry and now simply ACR), which was the first private registry for voluntary offsets in the United States.

Carbon offsetting under compliance mechanisms then took off with the Kyoto Protocol’s flexible mechanisms— particularly the CDM, which registered its first project in 2004. In parallel, but at a slower pace, the VCM grew. The private carbon standards that dominate the VCM today—VCS, GS, ACR, and CAR—emerged in the 2000s. The evolution of the VCM and of the four leading standards is depicted in Figure 1.1.

What is the status of the VCM?

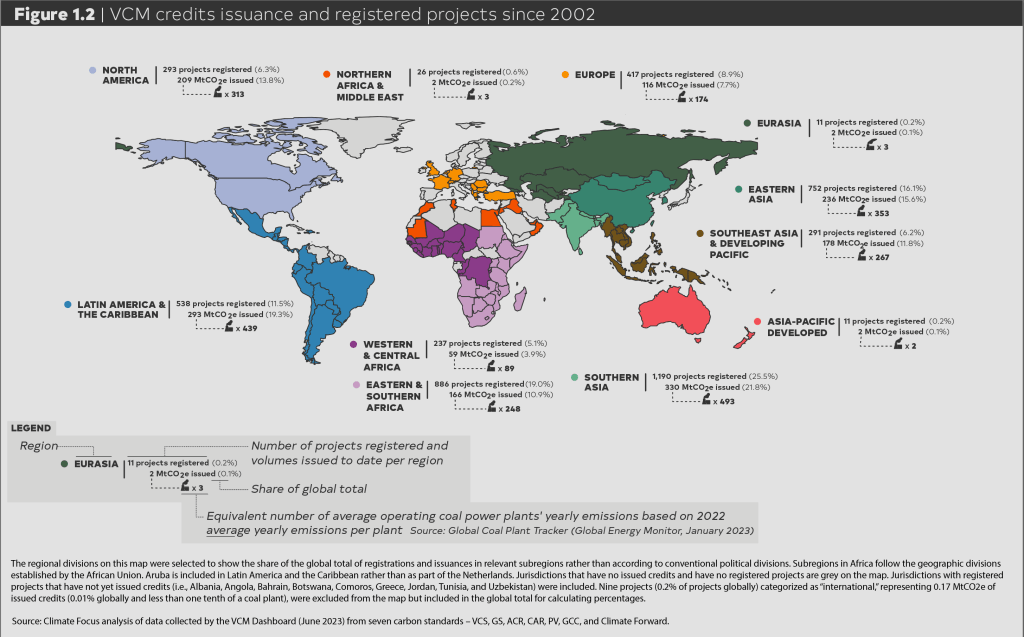

The status of the VCM can be understood in terms of growth of the market (Figure 1.1), geography and sector (Figures 1.2 and 1.3), and the volumes of carbon credits transacted and retired (Figure 1.4). The VCM is growing rapidly in both demand and supply. Growth in supply is evidenced by increases in the issuance of carbon credits and numbers of projects. Growth in demand is evidenced by increases in purchases and retirements (i.e., the use) of carbon credits. Most of the supply of carbon credits is generated in developing countries and most of the demand for carbon credits is in developed countries.

Supply

VCM issuances reached an all-time high in 2021 with 352 million credits issued. VCM volumes were lower in 2022, with 279 million credits issued, although 2022 was still the second largest year on record for the VCM. The slight decline in 2022 of the supply of VCM credits has been attributed to delays in issuances as carbon standards and auditors were overwhelmed with requests as well as to some governments pausing or halting VCM activities in their countries while they determine how they will apply Paris Agreement Article 6 rules. Concerns relating to the quality of carbon credits, the transparency of the market, and spurious carbon neutral claims have also made potential new market participants reluctant to engage in the VCM at a large scale. However, issuances remain high relative to historical levels and the overall volume of the VCM is expected to continue to grow. Globally, across all sectors, there are 4,661 VCM activities (projects and programs) that have generated 1,594 MtCO2e of GHG emission reductions and removals, which is equivalent to the average yearly emissions produced by about 2,384 coal plants (see Figure 1.2). Much of the supply of carbon credits comes from low- and middle-income countries.

At the regional level, Southern Asia is the top supplier of carbon credits overall, with many historic credits coming from renewable energy projects. Latin America and the Caribbean is the top supplier of nature-based solutions (NbS) credits. Africa accounts for most of the energy efficiency credits, the majority of which are generated by small-scale cookstove projects. Europe and North America contribute most of the credits from coal mine methane, industrial gases, and carbon capture and storage projects. At the country level, India, China, Brazil, the United States, and Indonesia are the top suppliers of carbon credits.

Greater numbers of projects does not necessarily equate to larger issuances of credits. This is shown in Figure 1.3. Southern Asia leads globally in number of projects and volume of credits, but in other regions the number of projects and volume of credits are not directly correlated. Community forestry, cook stove, or biodigester projects often result in many small projects because these activities are relatively quick to develop and can be added onto existing projects or groups of projects. These projects are often grouped in bundles or programs that are treated as single projects in Figure 1.3 but which could be further divided into individual projects. In contrast, REDD+ projects are often large, and single projects can be responsible for the issuance of large volumes of carbon credits. The most extreme case is Southeast Asia, where only 5.3 percent of projects are NbS but those deliver 73 percent of the issuances.

Demand

While the issuance of VCM carbon credits is increasing rapidly, it may not be sufficient to meet demand, especially for increasingly popular credits associated with agriculture, forestry, and other NbS. As the VCM continues to grow, it is likely that more credits from all types of projects will be generated to meet demand and carbon standards will continue to develop more robust methodologies for different types of projects.

The largest share of demand in the VCM comes from private companies that use carbon credits to contribute to their voluntary climate targets or market climate neutral products by offsetting the GHGs emitted by their production and activities. Consumers and public agencies acquire carbon credits to “neutralize” polluting activities such as travel or events. Further demand comes from regulations that allow liable entities to use VCM credits as compliance assets. Some governments allow companies to use carbon credits to meet obligations under carbon tax or emission trading systems.

One way to show the growing demand for carbon credits in the VCM is through credit retirements. Credits are retired when they are acquired by an end user and put towards offsetting carbon emissions or towards non-offsetting goals. If more credits are retired over time, then it is clear that there is a growing demand for that type of credit. Figure 1.4 shows that the volume of retirements has increased steadily since 2016. VCM retirements reached an all-time high in 2021, with 161.9 million retired.

The retirements of credits in the VCM shrunk slightly in 2022 relative to 2021. This has been attributed to an overall slowing of the global economy and to uncertainties associated with countries making decisions about Article 6 rules. However, 2022 set the record for second largest volume of retirements in any year, with 155.1 million credits retired. Demand for carbon credits is expected to remain high and continue growing.

What are the benefits and limitations of the VCM?

The VCM can mobilize foreign direct investment for climate change mitigation and sustainable development that is not provided through regulation. The VCM provides financing for climate mitigation projects that are complementary to governments’ efforts to mitigate climate change, and, in the case of jurisdictional REDD+ programs, to government mitigation initiatives. Today, almost all developing countries are seeing increased interest in VCM activities from project developers and carbon credit buyers. If used strategically, VCM finance can free up public funds to be re-directed into climate change mitigation goals that are not sufficiently incentivized by carbon finance.

There are two notable limitations of the VCM. First, the robustness of the VCM depends on the rigor that carbon standards apply when certifying real and additional emission reductions and removals. The quality of credits varies by the conservativeness of project quantification methods, the extent to which projects address uncertainty, and the inclusion of co-benefits such as contributions to Sustainable Development Goals. The methods applied to appropriately measure and monitor GHG reductions and removals are frequently revised and debated. As methodologies continue to improve, this limitation may be addressed.

The second limitation is that offsetting through the VCM is a supplementary measure that nets out emissions. It does not reduce emissions overall. As long as carbon credits are used solely to offset emissions, the VCM cannot provide a solution to climate change on its own. Non-offsetting uses for credits can help to shift the role of the VCM to a mechanism that drives emissions abatement.

Further Reading

- Almås, O., & Merope-Synge, S. (2023). Carbon Markets, Forests and Rights: An Introductory Series. Retrieved from https://www.forestpeoples.org/en/report/2023/carbon-markets-forests-rights-explainer

- Climate Focus & UNDP. (2023). VCM Access Strategy Toolkit. Retrieved from https://vcmintegrity.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/VCMI-VCM-Access-Strategy-Toolkit-1.pdf

- Dawes, A., McGeady, C., & Majkut, J. (2023, May 31). Voluntary Carbon Markets: A Review of Global Initiatives and Evolving Models. Center for Strategic & International Studies. Retrieved September 28, 2023, from https://www.csis.org/analysis/voluntary-carbon-markets-review-global-initiatives-and-evolving-models

- Mikolajczyk, S., & Bravo, F. (2023). Voluntary Carbon Market Update 2023 – H1: A Period of market consolidation. Retrieved September 28, 2023, from https://climatefocus.com/publications/voluntary-carbon-market-update-2023-h1-a-period-of-market-consolidation/World Bank. (2023). State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2023. Retrieved May 25, 2023, from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/39796

Acknowledgments

Authors: Melaina Dyck, Charlotte Streck, and Danick Trouwloon

Designer: Sara Cottle

Contributors: Felipe Bravo, Leo Mongendre, Laura Carolina Sepúlveda, María José Rodezno, and Theda Vetter

Date of publication: October 2023

The Voluntary Carbon Market Explained (VCM Primer) is supported by the Climate and Land Use Alliance (CLUA). The authors thank the reviewers and partners that generously contributed knowledge and expertise to this Primer.